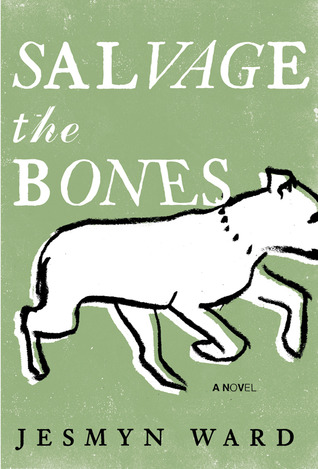

Salvage the Bones is the second mythology-soaked literary account of Hurricane Katrina I’ve read in the last few months, which is odd, and completely unintentional, as I picked this book up only because of good things I’d heard about its author, Jesmyn Ward. The narrative presence of the storm doesn’t even present itself until nearly a quarter of the way through, but the intertextual dependence the narrative has on the many different incarnations that the story of Jason and Medea has taken is quickly realized. The lack of any single authoritative plot with regard to that epic makes it an incredibly nimble framing device, as the reader not only can call on many shapes of the same story, but has no idea just exactly where the novel’s narrative might be compelled to go. Nifty.

Ward has studied with some literary heavy hitters, including my guy Tobias Wolff, and it shows in her prose. The novel is told from the perspective of a young black teen, and while there is nothing so flashy or ostentatious that it rings false, the voice is beautiful, observant and descriptive in metaphor and allusion. It’s quiet and well-paced, building up a narrative and a linguistic weight as the novel draws closer to its conclusion. There is no flab, no unnecessary sections or lines of thought or plot.

Continuing the theme of coincidence, I came across an essay on the debate about cultural ephemera in fiction, an essay that referenced both David Foster Wallace’s essay “e unibus pluram” -an essay that I had read perhaps a week prior- and this book, a novel that is directly time-stamped as it literally counts the days to Katrina, yet lacks virtually all reference to any work outside of the classics (a mention of Outkast playing on a car radio is the only thing I noticed). While there is plenty of opportunity to isolate the work in time and place, Ward chooses not to, chooses instead to tie it intractability to an ancient epic of no canonically defined narrative. While I must confess to be a bit standoffish with regard to an over-generous seasoning of pop culture references and the like, I think even a more objective reader would agree with me that these choices make Salvage the Bones an even stronger piece.